|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ashton "Jack" Worswick

|

Worswick tried to open his own shop in

1930. Perhaps due in part to the economic hardships of the

great depression, this enterprise must have been

short-lived, as records have him working for

Haynes-Schwelm in 1934, then back with Powell again in

1935. In 1936 Worswick again tried his hand at opening an

independent shop, which once again appears to have failed

quickly since he is listed working for William S. Haynes

in 1937 and for the next few years. The relocation of his

residence to Jamaica Plain several miles southwest of the

peninsula suggest he might then have worked for yet

another major Boston flutemaker, Harry Bettoney. During

WW2 Worswick worked for the war effort as a machinist in

the Boston naval yard. At the war's end he resumed

flutemaking for Wm. S. Haynes Co, where he practiced his

former craft from 1947-1953. Described by

acquaintances as "an elegant man," Ashton died in 1956 at

66 years of age. Worswick tried to open his own shop in

1930. Perhaps due in part to the economic hardships of the

great depression, this enterprise must have been

short-lived, as records have him working for

Haynes-Schwelm in 1934, then back with Powell again in

1935. In 1936 Worswick again tried his hand at opening an

independent shop, which once again appears to have failed

quickly since he is listed working for William S. Haynes

in 1937 and for the next few years. The relocation of his

residence to Jamaica Plain several miles southwest of the

peninsula suggest he might then have worked for yet

another major Boston flutemaker, Harry Bettoney. During

WW2 Worswick worked for the war effort as a machinist in

the Boston naval yard. At the war's end he resumed

flutemaking for Wm. S. Haynes Co, where he practiced his

former craft from 1947-1953. Described by

acquaintances as "an elegant man," Ashton died in 1956 at

66 years of age. |

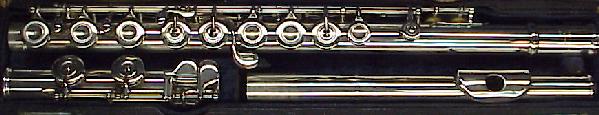

The Worswick Flute/Boston/10 displays the

understated elegance of the best handmade Boston flutes of

the period, perhaps rather more like an early Haynes than

a Powell in mechanism design and finish. Toneholes, points

and posts are fitted and soldered with the care one would

expect from an artisan intent on impressing a potential

clientele in the city which already laid claim to some of

the best flutemakers in the world. The Worswick Flute/Boston/10 displays the

understated elegance of the best handmade Boston flutes of

the period, perhaps rather more like an early Haynes than

a Powell in mechanism design and finish. Toneholes, points

and posts are fitted and soldered with the care one would

expect from an artisan intent on impressing a potential

clientele in the city which already laid claim to some of

the best flutemakers in the world. |

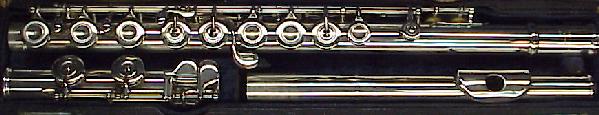

Susan Berdahl ended her narrative on

Ashton Worswick with the statement, "No Worswick Flute

Company flutes are known to exist." At that time

this flute was safely ensconced in the closet of Ed

Ransom. His parents (both graduates of the Art Institute

of Chicago) located this flute in a shop in the Chicago

area in the early 1950's and purchased it for Ed to play

in the 7th grade. Ed was kind enough to pass this bit of

flute history along to me. Solder joins appeared sound,

mechanism sluggish but solid, less worn than many flutes

of similar vintage (perhaps due to its long retirement).

Pads, corks and shims were shot and a hodgepodge of spring

types hint at earlier work done to the flute over the

years. Susan Berdahl ended her narrative on

Ashton Worswick with the statement, "No Worswick Flute

Company flutes are known to exist." At that time

this flute was safely ensconced in the closet of Ed

Ransom. His parents (both graduates of the Art Institute

of Chicago) located this flute in a shop in the Chicago

area in the early 1950's and purchased it for Ed to play

in the 7th grade. Ed was kind enough to pass this bit of

flute history along to me. Solder joins appeared sound,

mechanism sluggish but solid, less worn than many flutes

of similar vintage (perhaps due to its long retirement).

Pads, corks and shims were shot and a hodgepodge of spring

types hint at earlier work done to the flute over the

years. |

Surprisingly, the only major sign of truly

outrageous fortune is an odd longitudinal dent in the

headjoint that at first appeared to be delamination of a

seamed tube but, extruded tubing being the norm for flutes

of this period, further inspection revealed the obvious.

The damage was no doubt caused by improper and energetic

use of a swab stick, perhaps to adjust the cork placement.

The headjoint nonetheless spoke well when used in a body

in better repair, with a resistance and tonal color not

unlike a very early Powell. Surprisingly, the only major sign of truly

outrageous fortune is an odd longitudinal dent in the

headjoint that at first appeared to be delamination of a

seamed tube but, extruded tubing being the norm for flutes

of this period, further inspection revealed the obvious.

The damage was no doubt caused by improper and energetic

use of a swab stick, perhaps to adjust the cork placement.

The headjoint nonetheless spoke well when used in a body

in better repair, with a resistance and tonal color not

unlike a very early Powell.Following a proper overhaul by Harold Phillips at J. L. Smith & Co., the mech is light and tight without the "fragile" feeling of some older flutes, and the crease in the headjoint has been smoothed down to near invisibility. I agree with Larry Woodall, who performed a similar resurrection on his Worswick #7: "the Worswick flute plays fantastically ... as good or better than any Powell or Brannen." It is a real player with good intonation (if you can stay away from the A=442+ ensembles) and a responsive and strongly centered voice from low C on up into the somewhat reserved third octave. If only Mr. Worswick had picked better economic times to strike out on his own -- and maybe changed his name to something a bit easier to remember -- he might have taken his place among the best of the Boston makers. |

Return to GoferJoe's Flutes

Return to GoferJoe's Flutes Thanks to Ed Ransom and

Susan Berdahl for the lesson in flute history.

Images © J. W.

Sallenger.